Microphone. Power supply. Shock mount. Windscreen. Pistol grip. XLR cable. Headphones. Recorder. Bird.

All of these things work together to capture a bird song. Following Audubon’s Guide to Recording Bird Song, I scoured the internet to put together my own secondhand bird recording kit.

Determined to step up my recording game from my previous attempts, I set out to Brackenridge Park in the early morning light with my new equipment to take it for a spin and see if I could get some high-quality sound bites.

I arrived at the park just before 8 AM. A final check of my equipment and I was on my way. Slowly, with the microphone and recorder in hand, I exited the car and scanned my surroundings. I looked at the park with what felt like fresh eyes: ignoring large groups of quiet birds, sensing the wind speed and direction, looking for individual birds singing far from noisy distractions, searching for birds that might start to vocalize. These were things I hadn’t focused on in my previous bird outings.

The garbage bird of San Antonio

My first target was quickly identified: the resident garbage bird of San Antonio–the Great-tailed Grackle. There it was, sitting atop a dormant tree in the middle of the parking lot, screaming its little heart out.

Fumbling, I slipped my headphones over my head, fired up the microphone, and pointed it up at the tree like a handgun. Instantly clear sounds of the grackle began flooding into my headphones. I stood there in this pose for two minutes until my arm started to ache. Satisfied, I stopped the recording and tried to listen for the next target bird. This is where the challenges began to manifest.

More gear. More problems.

If you’re keeping track, right now I’m managing a microphone tethered to a recording device tethered to a pair of headphones. This makes things quite cumbersome when you need to constantly put on and take off your headphones.

Locating birds while wearing headphones is near impossible

While it would have been nice to just keep the headphones on the entire time I was at the park, it was completely impractical. Once I was finished recording the grackle, I tried to listen to other birds around me. While I definitely could hear them, without the full use of both my ears it would be challenging to pinpoint them. That said, it was necessary for me to keep them off while walking around.

Walking further into the park, I spotted a few large Black Vultures sitting on a chain-link fence across the parking lot. I haven’t been close enough to them before to know if they make any kind of noise. Thirty seconds into recording one confirmed that it wasn’t about to make any sound. Dud.

Love is in the air

Brackenridge Park has many picnic tables and a pavilion next to a playground. I wandered over there to see what kind of birds may be nearby. Coooo….coooooo…. *head up* *head down* *twirl*. Next to the pavilion, a flock of Rock Pigeons was walking around. Several of the male pigeons were doing their mating dances and cooing for the nearby females.

Non-vocalizing sounds

Unsure of whether this would be a “desired” type of clip, I spotted a Double-crested Cormorant swimming on the water and began recording it. Listen closely to the below clip and you’ll hear some splashing as it dives underwater and then about 10 seconds later it resurfaces to swallow a small fish.

Nature’s aviation light

Thirty feet away perched at the top of a tall, green tree was a male Northern Cardinal. Its bright red color shone in the light and reminded me of the bright red aviation lights seen on the tops of tall buildings to keep planes away. This particular bird was singing his favorite song for the whole park to hear.

After I returned home, I fired up my computer and transferred over all of my new sound clips. I’ve been using Ocenaudio to analyze and edit my audio clips. It’s a free application recommended by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Editing bird songs

Ocenaudio enables you to view spectrograms, apply filters to reduce background noise, and trim your audio clips. Cornell has a handy guide that you can follow to learn some tips on how to edit bird songs. I’ve also written a quick summary of how I edit my bird photos. Like with photo editing, less is more, don’t over-edit audio clips. Scientists find the most value when clips are left as natural as possible.

Uploading bird songs online

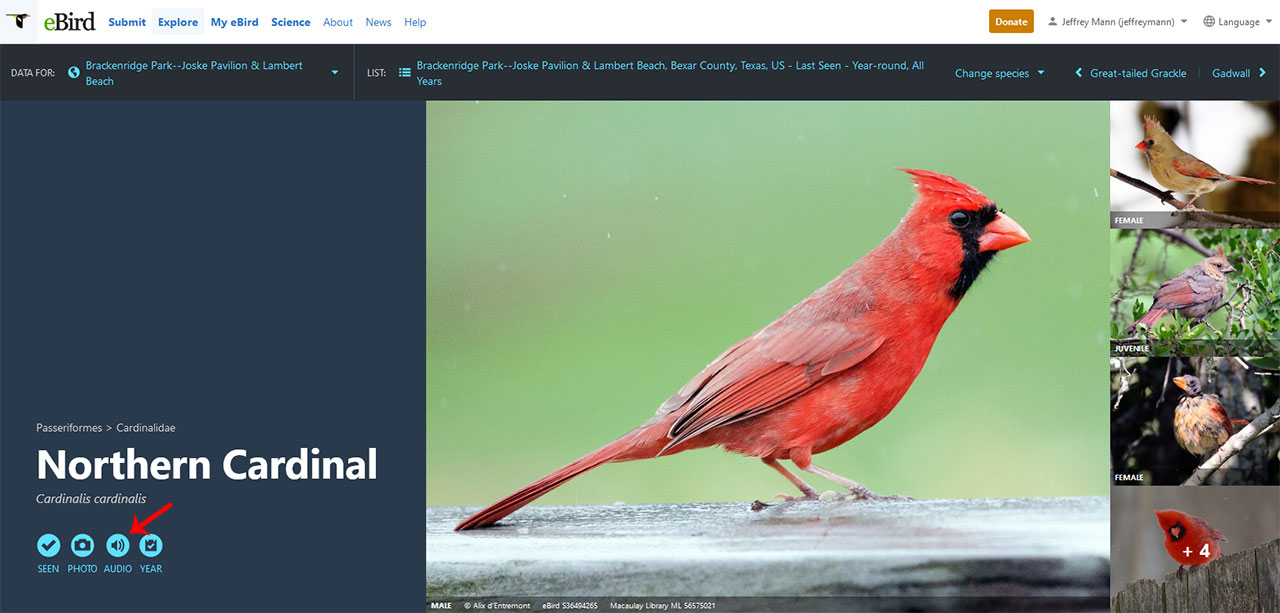

Your bird song clips should be uploaded to eBird just like your photos. After making any necessary edits to your audio clips, they can then be attached directly to your eBIrd checklist. These clips automatically become a part of the Macaulay Library and help contribute to science and conservation. You’ll also get a sweet new audio badge on any species page for which you’ve uploaded audio clips.

Species page photo

Have you recorded bird songs before? Write to us and let us know what your experience was like.

Hello Jeff,

Please guide me to the proper cable (new at recording bird song) to connect a Senn. ME66 with K6 power module (i will start with AA batteries) to my late model iPhone with Lightning input?

I appreciate all you have taught me and many others.

Very best,

Alan Mitcnell

Hi Alan!

I made a post describing connecting my ME66 to the iPhone. I hope you find it helpful. It requires some adapters but I was able to get it working with Merlin.

I would also highly recommend connecting the microphone to a dedicated recorder. This will give you control of the gain and can produce better recordings.

Jeff